The Sword Without, The Famine Within

June 28 – August 3, 2019

François Ghebaly

2245 E Washington Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA

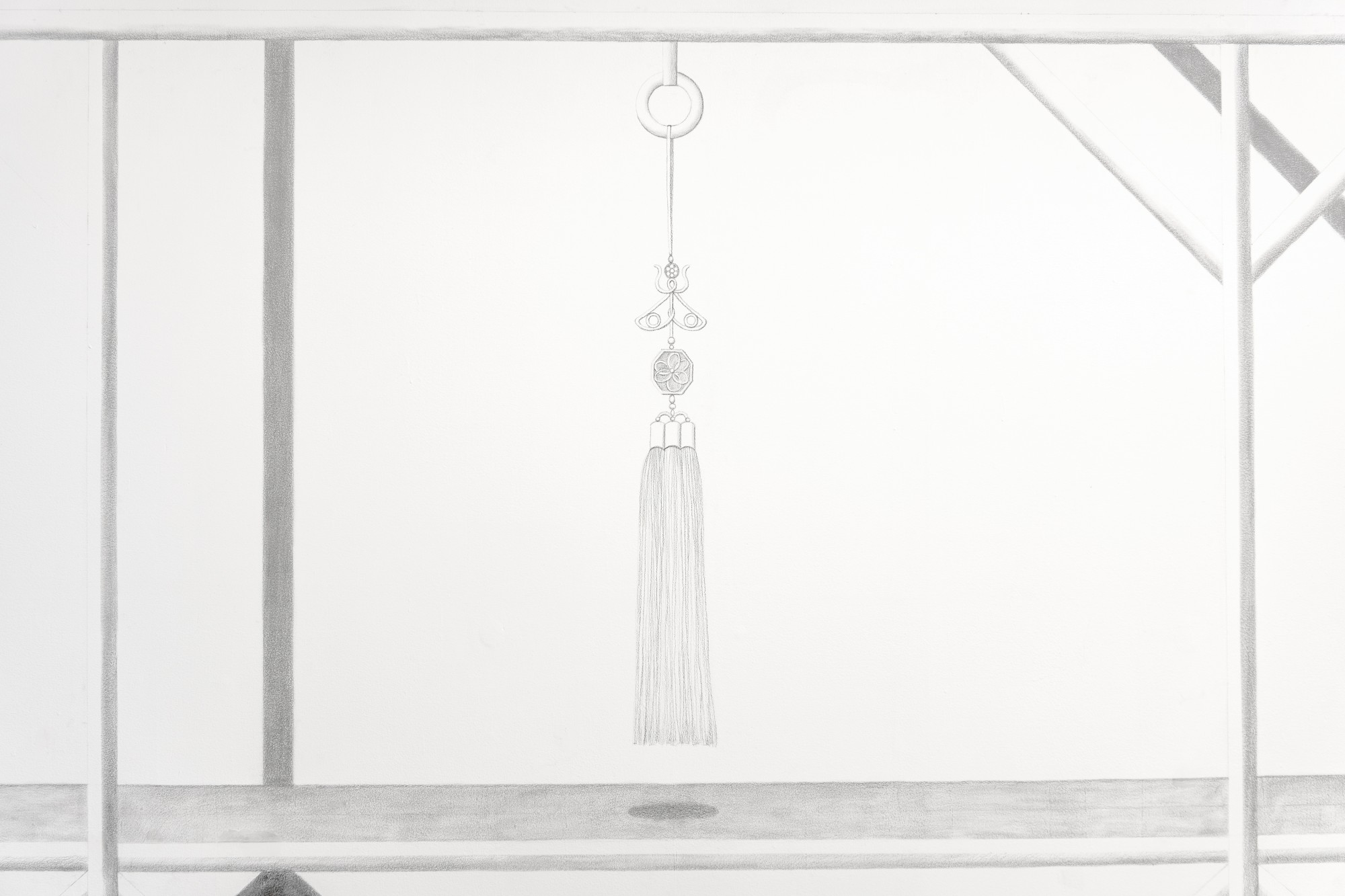

Crux Simplex: a Metal Image, a Teacher of Lies. 2019. 63' x 12'. Graphite and acrylic on wall

Crux Simplex: a Metal Image, a Teacher of Lies. 2019 (detail)

Crux Simplex: a Metal Image, a Teacher of Lies. 2019. 63' x 12'. Graphite and acrylic on wall

Installation view: The Sword Without, The Famine Within, Francois Ghebaly, Los Angeles, 2019

Human Heart is a Factory of Idols. 2019. 96" x 72". Oil, acrylic, ink, graphite and oil pastel on canvas

Human Heart is a Factory of Idols. 2019 (detail)

I Heard Nothing But Laughter. 2018. 84" x 64". Oil, acrylic, ink, graphite and oil pastel on canvas

I Heard Nothing But Laughter. 2018 (detail)

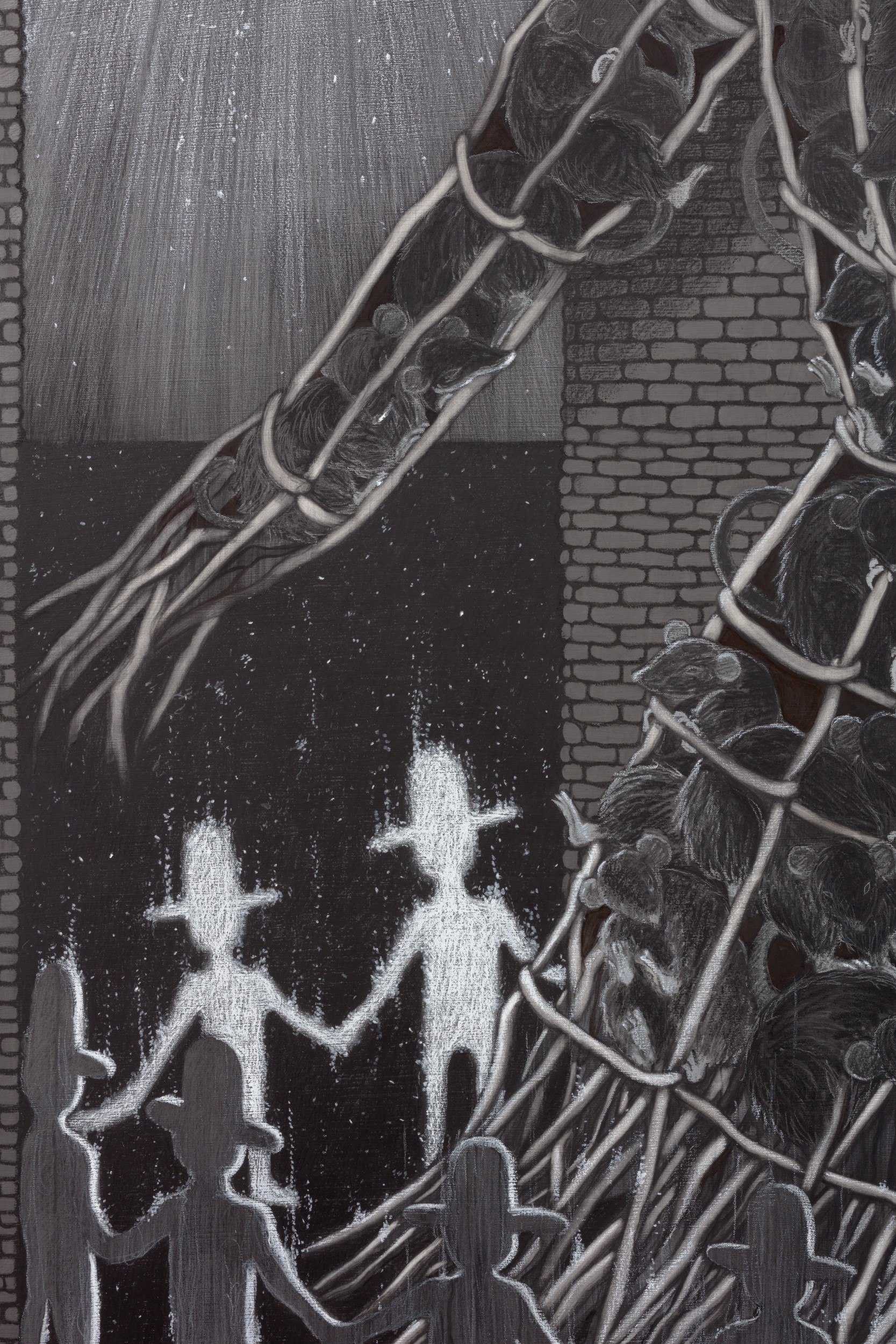

The Binding of Isaac. 2018. 84" x 64". Oil, acrylic, ink, graphite and oil pastel on canvas

The Binding of Isaac. 2018 (detail)

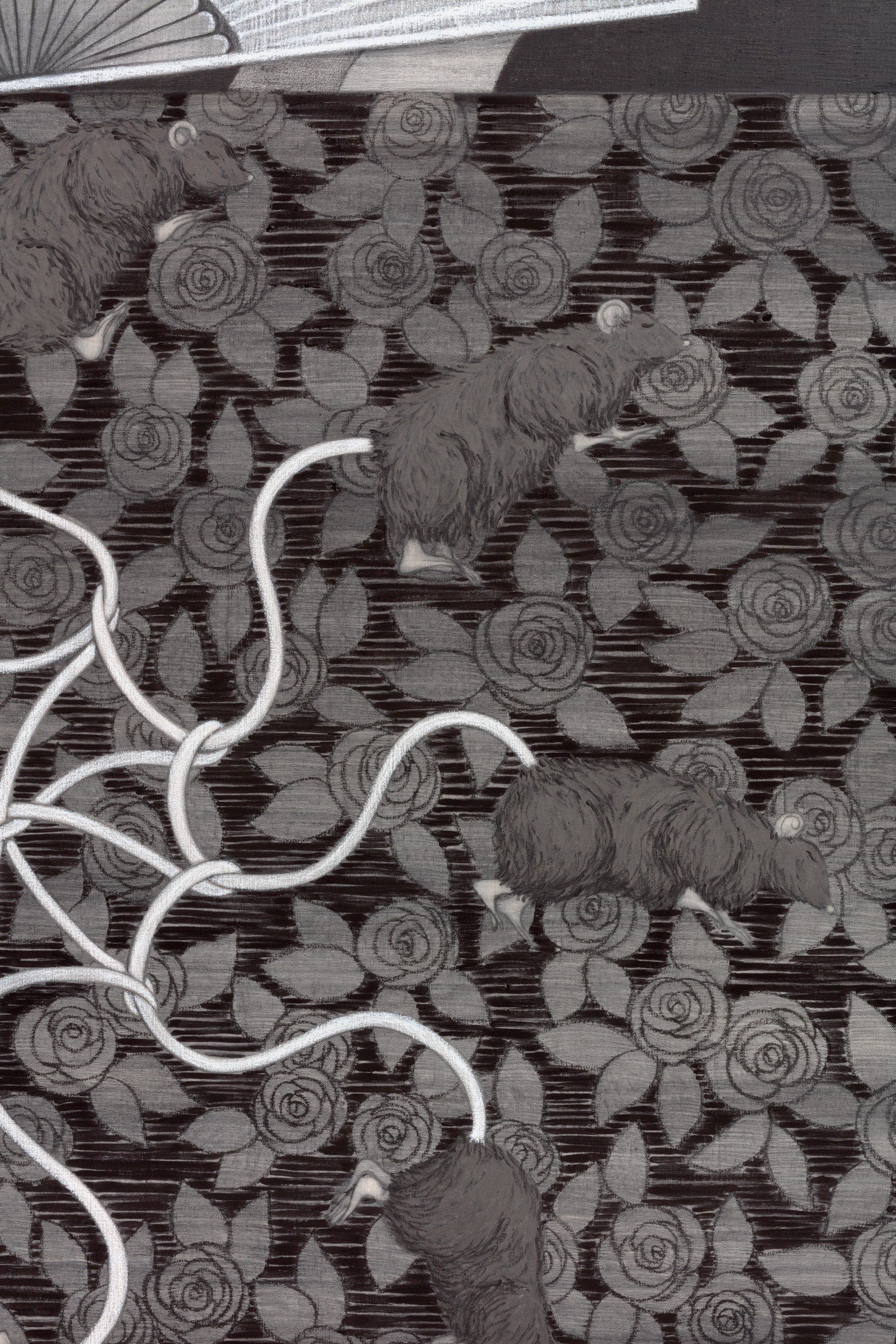

Butterflies Will Make You Blind. 2018. 84" x 64". Oil, acrylic, ink, graphite and oil pastel on canvas

Butterflies Will Make You Blind. 2018 (detail)

Installation view: The Sword Without, The Famine Within, Francois Ghebaly, Los Angeles, 2019

This story could be called ‘The Statues.’ Another possible name is ‘The Murder.’ And also ‘How to Kill Cockroaches.’ So I will tell at least three stories, all true because they don’t contradict each other.

— Clarice Lispector, “The Statues”

There are no cockroaches or statues in Cindy Ji Hye Kim's The Sword Without, The Famine Within, yet both Lispector's short story and Kim's own work converge on remarkably similar meta-fictions. Lispector's protagonist kills cockroaches with a paste of nutrients and plaster, mummifying them from the inside out and turning their inert bodies into prisms that refract the story into countless potential narratives. For Kim, one and a half sticks of charcoal, a quarter-pound of Van Dyke brown and a half-pound of iron oxide and graphite, crushed and broken into the canvas, serve the same function as the poisoned bait: an act of lethal ossification by which corpses stabilize into a new alphabet that endows the community with a rejuvenated capacity for writing stories.

Kim’s paintings are not acts of spontaneous generation, manifestations ex-nihilo from within the imagination, but a sacred place of destruction. Creation, healing, regeneration only takes place in the acts of interpretation that emerge from the ashes as a new mythology. The making of the work, both the painstaking labor and the expenditure of raw material, is always a sacrifice of the artist’s inherently finite means; the work itself is simply a way of concretizing otherwise invisible affects among the group and opening up repressed wounds in the service of catharsis.

There is always, as such, a deep negation in craftsmanship. But while the artist doesn’t control the evolutions of meaning that happen around their act of self-mutilation, they nonetheless have chosen the kind of catalyst into which they shape their pound of flesh. Neither artists nor works of art are vessels that “contain” meanings: they are surfaces through which narratives burn. An idea only “means” something insofar that we vote with our feet and pay a price, and to create new significations requires that we immolate the very structures that circumscribe our identities.

At the end of the day, one must submit to the tactile throw of the die—how could any of this simply make “sense” on its own? To grope for content “inside”, for an alleged “truth” beyond the relentless unfoldings of our volition, would be to suppose ourselves hollow, heads filled with the very kindling and wicker that burns the beasts we prepare for slaughter.

Of what profit is an idol when carved by a craftsman; a metal image, a teacher of lies? For its maker trusts in his own creation when he makes a speechless God.

— Habakkuk 2:18

Alexander Boland, 2019

As a figurative painter I'm interested in the process of raw materials transforming into signs and symbols on the surface of a painting; One and a half sticks of charcoal, a quarter pound of Van Dyke brown, and a half pound of ironoxide and graphite, have all been crushed and broken into the canvas, molded into images of the moon, the goat, and everything in between the unconscious and the unknown. It's kind of like ink becoming letters, words, and stories on a page.

For the four paintings in the show, I see each of them first and foremost as a place of slaughter and a sacred place of destruction. As a believer of images, the rebirth of these supposedly "killed" materials takes place in the realm of metaphors. The analysis and interpretation are mere stories, necessarily so, that bind us together, from me to you, from past to present.

For the longest time I thought art-making was a practice of giving material forms to intangible things like ideas, memories, or emotions that consciously or unconsciously resided in my psyche. A positive and creative process. And vice versa, my art objects were to be seen as if containing all that was invisible, embedded meanings to be mined, deciphered, and to be interpreted.

I found sacrificial ritual as a refreshing perspective to reexamine this equation of art object and meaning production I had set for myself. Sacrifices are communal activities that expiate the sin of the community, a ritual that points to the shared anxieties and insecurities of a group. The act of destroying calves, virgins, women, criminals, or marginalized members of the group – was a way of giving these invisible feelings a concrete form.

I think my initial interest in sacrificial practices was that these rituals resembled so much of the practice of painting - the gesture of isolating elements and giving them a concrete form. Either isolating a convict or a possessed, sacrifice is about locating the invisible emotions, ideas, and memories of a group onto a thing, an animal, or a person. But the gesture of making the invisible, ultimately visible by destroying it - either as an offering to God, or as a punishment - is something totally opposite to art-making which is a positive material creation. Sacrifice requires the theatrics of material destruction to gain any kind of meaning.

This is where I saw the connection to image-making, the process in which materials die when it enters the realm of metaphors. I like taking the stance that I'm a believer of surfaces and not of substances. As a figurative and representational painter whose job is to create and forge imitations - contrary to iconoclasts or modernists who would like to see materials pure or depictions of God unadulterated - I see my painting as a place where materials come to die. I think this is why I see my paintings as corpses.

The only difference I would say between a sacrifice and a painting is that while the theater of sacrifice is used as catharsis or as a tool to soothe the crowd, art does not heal anyone or anything in my opinion. To me art opens up wounds and sprinkles salt over it. I think narratives heal. And that’s what historians or analysts do, but not the artwork.

Cindy Ji Hye Kim, 2019.

Press release by Alexander Boland

Photography by Lance Brewer