List Projects: Cindy Ji Hye Kim

October 29 – September 12, 2021

MIT List Visual Arts Center

20 Ames Street

Cambridge, MA

Back: Double-Tongued Citadel. 2020. 32’5” x 10’4”. Graphite and acrylic on wall

Front: Superego Fortuna. 2020. 68" x 54". Graphite, charcoal, pastel, ink, acrylic, and oil on silk.

The Body Sins Once. 2020. 96" x 1 1⁄2 " diameter. Carved hemlock wood

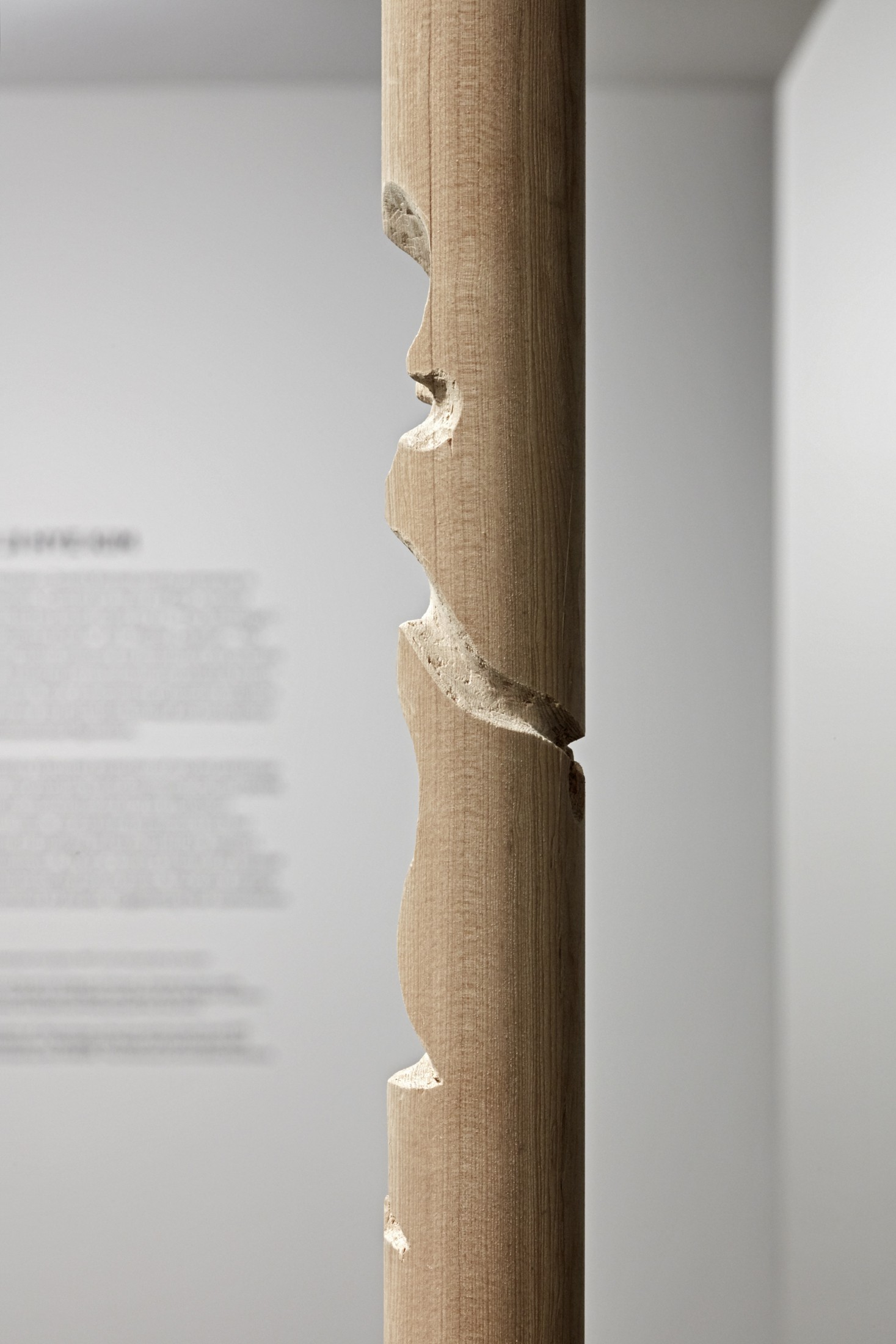

The Body Sins Once (detail). 2020. 96" x 1 1⁄2 " diameter. Carved hemlock wood

The Body Sins Once (detail). 2020. 96" x 1 1⁄2 " diameter. Carved hemlock wood

The Body Sins Once (detail). 2020. 96" x 1 1⁄2 " diameter. Carved hemlock wood

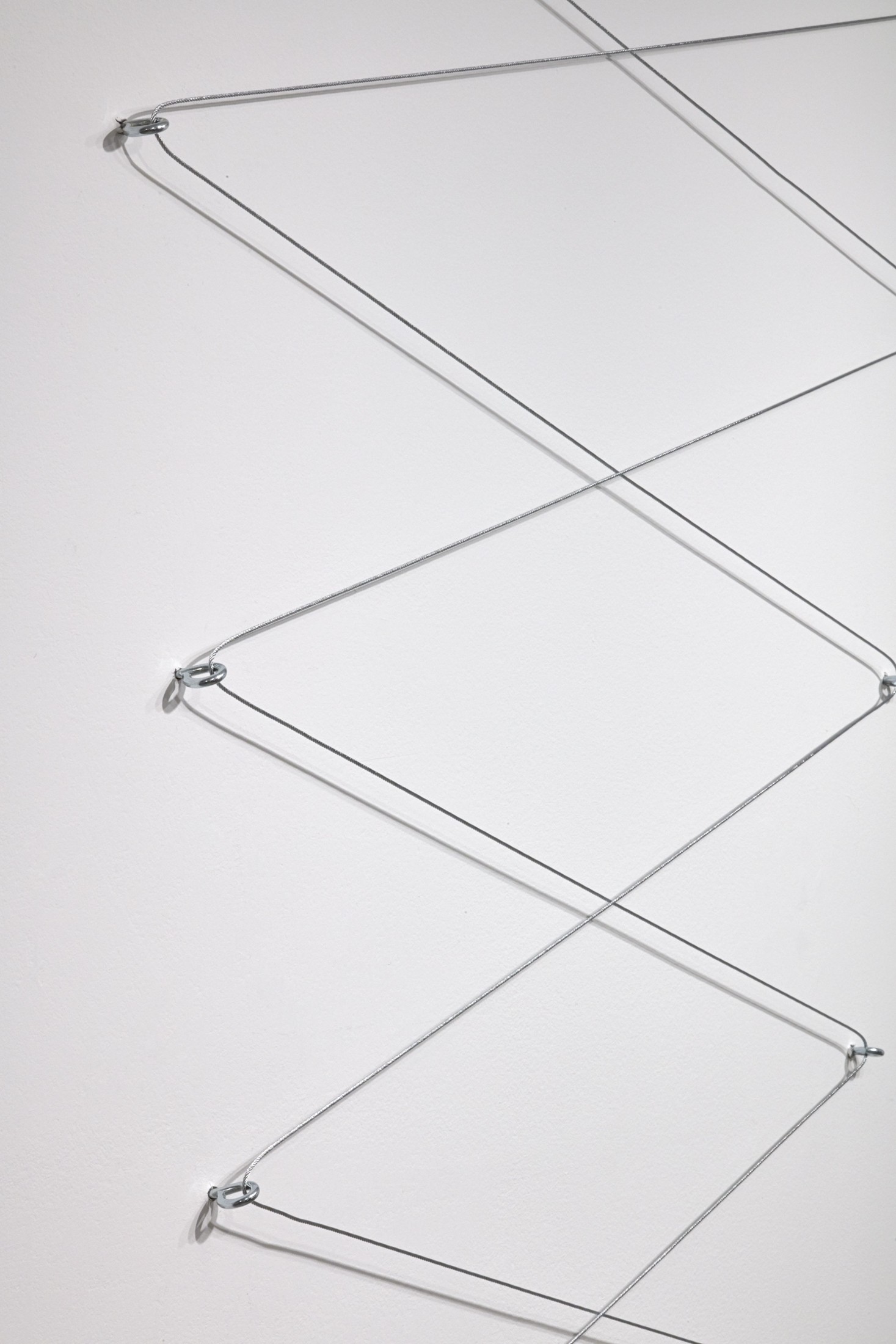

Iron Nerve. 2020. Dimensions variable. Steel cable, screw eyes

Iron Nerve (detail). 2020. Dimensions variable. Steel cable, screw eyes

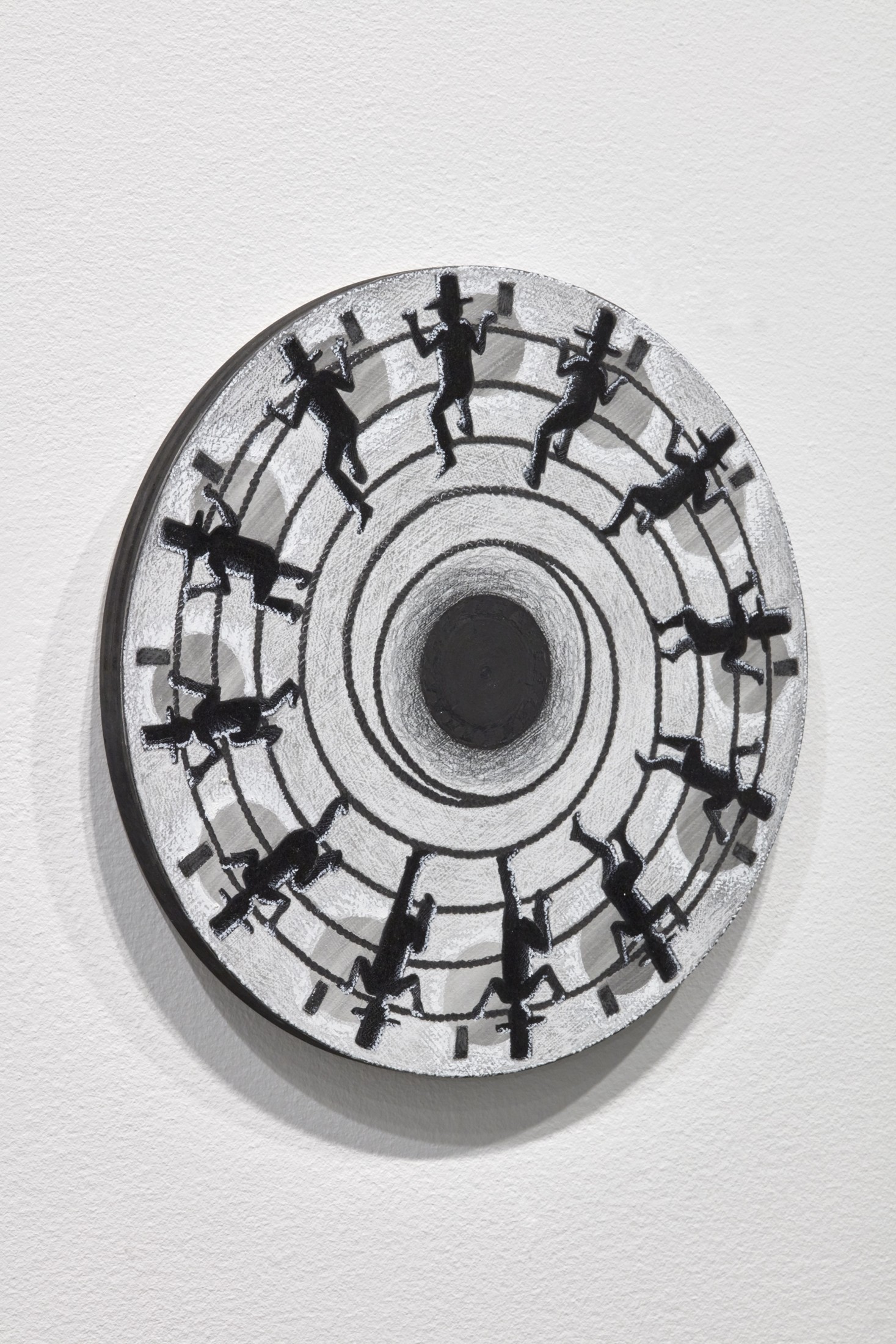

Reign of the Idle Hands #1. 2019. 12" diameter. Oil, acrylic, ink, pastel, charcoal, graphite on birch

Reign of the Idle Hands #2. 2019. 12" diameter. Oil, acrylic, ink, pastel, charcoal, graphite on birch

In Cindy Ji Hye Kim’s recent paintings, stylized figures—graphically rendered with bold, illustrative lines—are contained by restrictive or provisional structures like scaffolding, gallows, and theatrical lighting rigs. Referencing a wide range of art and visual culture, from the styles of propaganda posters to early black-and-white animations to painterly representations of biblical narratives, her works exploit the strategies of image making with a critical attention to their conventions. Kim’s sometimes gruesome subjects probe the body’s relationship to architectures of power, while articulating formal and conceptual relationships between the content of her images and the technical limitations of two-dimensional representation.

Reign of the Idle Hands (2019), a series of small round paintings, is informed by the phénakistoscope, an early animation disc that when rotated around a central axis gives the illusion of movement to the images drawn on its surface. In these works, Kim disables the apparatus central to their concept. Presenting the mechanism of the technology, rather than its effect, repeated forms are trapped in poses that are each a fragment of what, if activated, would be a cohesive motion. Here, and in many recent works, Kim employs a greyscale palate known as grisaille, a technique that has historically been used for artist’s drafts or depictions of classical sculpture, or as an underpainting scheme over which other pigments are layered. Kim’s commitment to grisaille yields images with a hint of cinematic noir, while her restrictive palette mirrors the sense of confinement her subjects face. Her series of “Character” paintings, for instance, depict figures contorted into positions that resemble Hangul (letters of the Korean alphabet). Hemmed in both by scaffolding depicted in the image and the physical boundaries of the canvas, these figures are objectified and transformed into linguistic signifiers.

Just as the artist’s considered use of grisaille exposes the often-hidden, technical elements of painting, figures carved in silhouette in the stretcher bars of hanging paintings such as Mister Capital, and Madame Earth (both 2019) call attention to the back side of a canvas, which is otherwise typically concealed. As Kim’s works exhaust the spatial possibilities of the stretched canvas and the flat and bounded picture plane, they also engage these visible architectures as analogues for unseen structures of power, intimating that one’s subjection to such forces is both integral and by design.

Organized by Selby Nimrod, assistant curator, MIT List Visual Arts Center.

Photography by Charles Mayer

Select Press

DOWNLOAD

— Press Release